Can a Company Create a Moat Using Patents?

Can patents create an economic moat, or in other words, an entry barrier for a company? If so, how? Let’s dive in.

Written by Shohei Hirota, Edited by the Universe Editorial Team

My name is Shohei Hirota and I offer IP-related support to our portfolio startups at Global Brain (GB).

In the course of supporting our portfolio companies, some startups ask me whether patents can create an economic moat, and if yes, how they should get to work. I decided to gather my thoughts around this.

The importance of patents differ among sectors

Although patents generally have positive impacts on sectors like drug discovery and materials, they are less important in businesses that handle hardware or software technologies. Especially in software businesses such as SaaS, patents are considered even less critical.

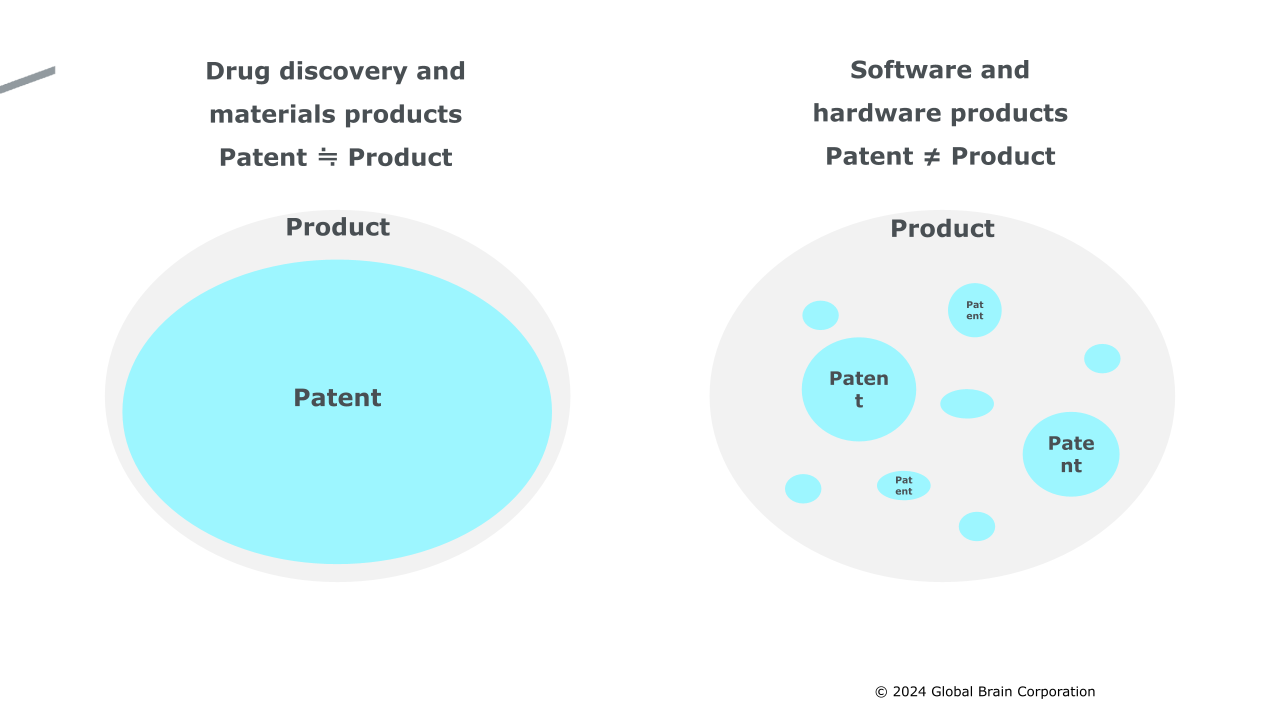

In drug discovery and materials sectors, the patents acquired for materials are equal to products. A few patents can sufficiently protect the product itself. However, with hardware and software products, the product is not equal to a patent. A patent merely protects part of a product, meaning you normally have dozens or up to several hundreds of patents for one single product.

The scope and enforcement of each patent is different depending on its quality. If you are handling hardware or software products, you would have various patents with both broad and narrow claims. As a result, patents in these sectors are considered relatively less valuable.

The lower your technological advantage, the more you need a moat

From a different point of view, an economic moat is indispensable if your product can easily be copied using technology. If that is the case, the impact would be huge if you could patent a critical feature of your product.

With most software services such as SaaS, it is easy to imitate the product as long as you have the money and engineering resources. Plus, even if you are a pioneer in a market with high growth potential, the higher the potential of the market the more followers and entrants it will have, which poses risks for your business. This is exactly where a moat comes into play. The key here is how you create a moat. In such a situation, if you could acquire a patent to create a moat, that would be very valuable for your business.

That said, can patents create a moat in sectors other than drug discovery and materials? Let me describe what perspectives we need to take into account.

Patents, moats, and competitive advantage

One single patent cannot cover everything. This is true for almost all sectors. One patent alone cannot create a big moat. But what is a big moat to begin with?

Peter Thiel, founder of PayPal, lists four characteristics of monopoly in his book Zero to One.

-

Proprietary technology

-

Network effects

-

Branding

-

Economies of scale

We can say that satisfying these four conditions creates a big moat.

However, when we think of patents, proprietary technology may seem like the only relevant characteristic out of these four, and even that may be limited to the so-called deep tech companies. Does that mean the other three are irrelevant?

To benefit from network effects, branding, and economies of scale, you need to put in many hours and effort. Network effects work at scale. You need to have more people use your products and services. Then your user base will grow, creating a strong brand and letting you enjoy the economies of scale.

In short, the size of your user base and retention rate have deep relevance to the other three characteristics.

Following this train of thought, we can say that patenting and protecting features and technologies that contribute to Product-Market Fit (PMF)*1 = “having more users continue to use the product” could turn into the building blocks of a big moat, even if each single feature cannot create a big moat on its own. So how do we use patents to protect features and technologies for PMF? Let’s dig in deeper considering the connection with Total Addressable Market (TAM)*2.

*1 Product-Market Fit describes a state in which a company is offering products that solve the users’ issues, and the products are accepted by an appropriate market. *2 Total Addressable Market describes the total revenue opportunity within a market for a business.

Patents and expanding TAM with PMF

Looking across recent software services, we understand that one specific feature alone cannot cover massive markets and customers anymore. Video conferencing and messaging tools as represented by the likes of Zoom and Slack are among the few that created their own respective businesses and markets with one single feature. But even Zoom is differentiating itself from competitors by adding multiple new functions such as the scheduler extension, webinars, and interpretation/translation.

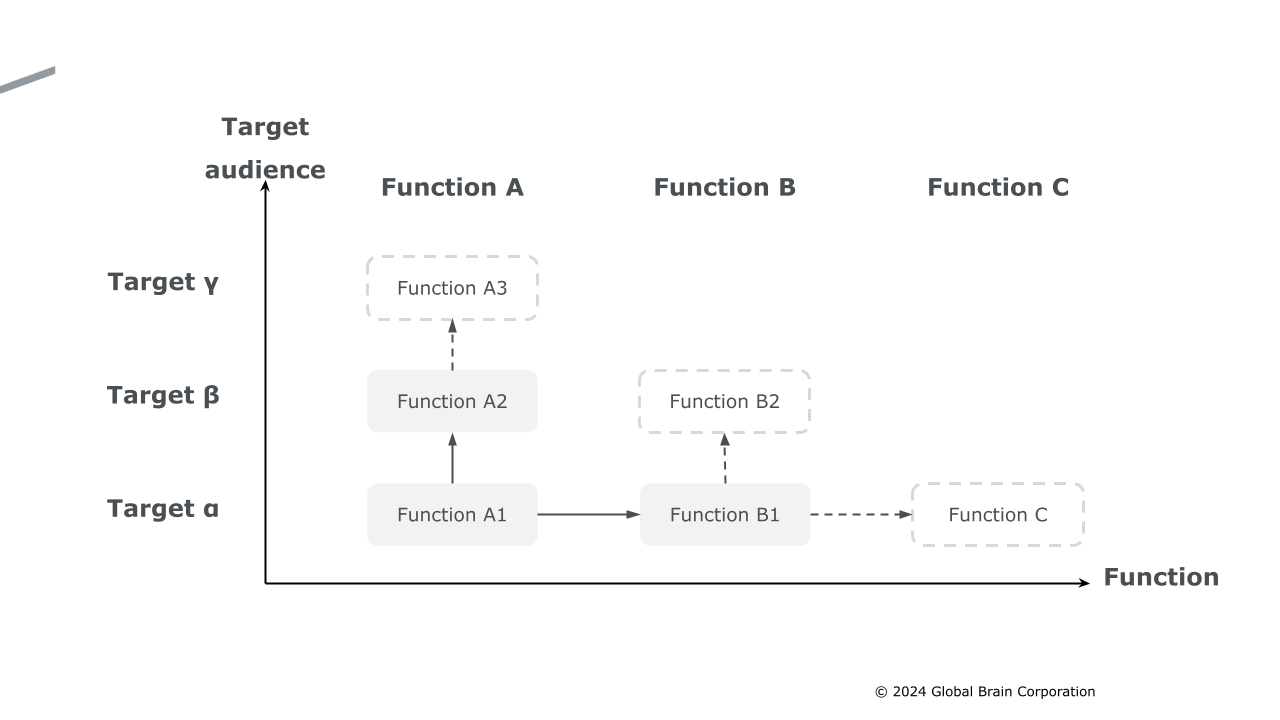

Here we look at the relationship between PMF and TAM by taking functions on the x-axis and target audience on the y-axis.

Let’s first assume that we launched a business by offering Function A1 to Target Audience α. To Target Audience α, we can aim for business growth by improving ARPU/ARPA and reducing customer churn by offering Functions B1 and C1. Then we shift our aim to Target Audience β, to whom we offer Funcion A2, a customized version of A1. With this, we could potentially achieve PMF with Target Audience β, and happily expand our TAM.

This is a scenario where each feature contributes to small-scale PMFs and all the features and functions contribute as a group to PMF in a larger market. In such cases, filing patents along the way as the business achieves PMF and expands its TAM could create a big economic moat for the company. Now, let’s take SmartBank’s B/43 as an example.

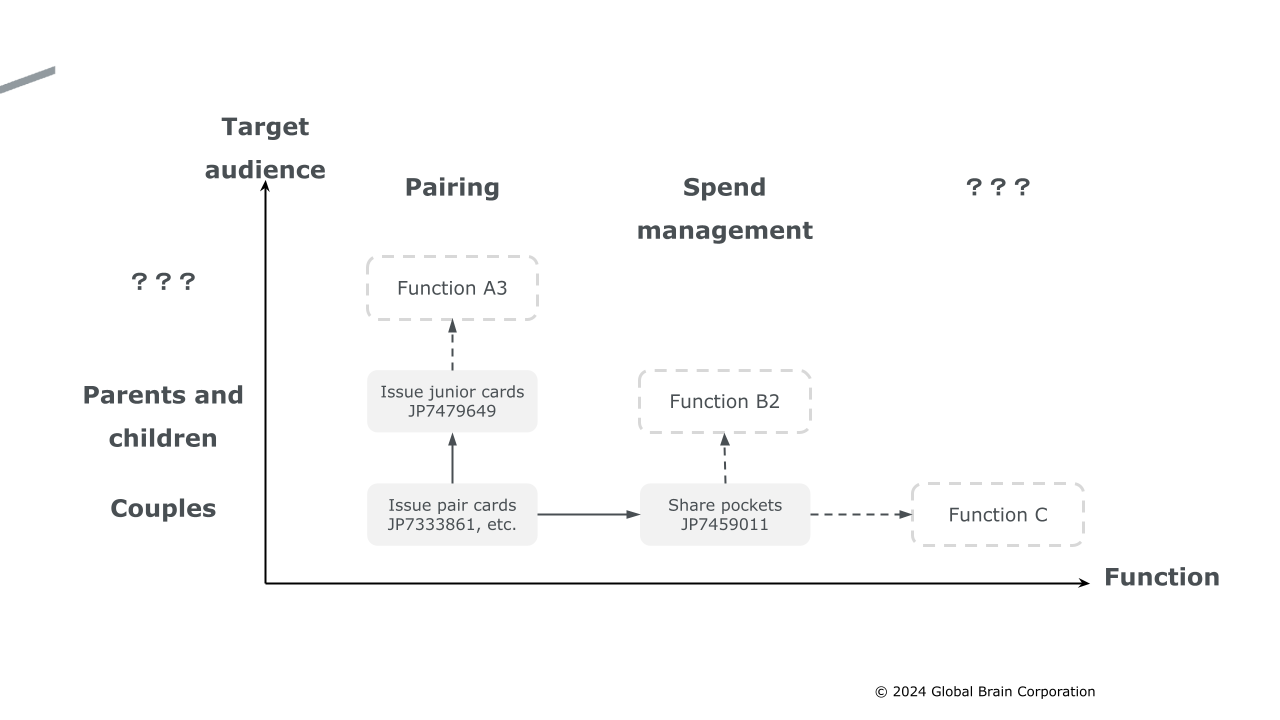

B/43 offers prepaid cards for couples and holds patents for its pairing feature (JP7333861 and JP7195031) and subaccount (named “Pockets”) sharing feature (JP7459011). The company is also planning to patent its feature for junior cards targeting child users that can be paired with the child’s mobile device allowing parents and their kids to share payment histories. (JP7479649).

The target audience x function matrix spells out the key functions for SmartBank, which they protect using multiple patents. This at least makes it more difficult for competitors to replicate the service.

While keeping market followers at bay, SmartBank is able to go ahead of others by offering pair cards and junior cards that have high switching costs. They can enjoy the benefits of its branding power and economies of scale, and continue to create its economic moat. I recommend you to check CEO Shota Horii’s article (in Japanese only) which describes B/43’s moat and also touches upon patents.

Defending which position?

I would like to move on and explain the patent-moat relationship from one more different perspective.

If you have incumbents in a specific market, you might try to differentiate yourself by positioning yourself uniquely. When doing so, you need to think about what exactly is the position you want to establish for your company.

Here, we will look at Luup as an example.

Luup is a sharing service for e-scooters and e-bikes. Since Docomo Bike Share was the pioneer in e-bike sharing, Luup entered the mobility sharing service as a market follower.

As explained in this article (in Japanese only), Luup strategically aims to increase the density of its parking stations. Setting up more stations to improve convenience can yield an increase in the number of users, which then allows the company to add even more stations. This cycle of growing both the number of stations and users creates network effects, leads to economies of scale, and creates a big moat for the company.

Among the over 10 patents filed by Luup, one patents a reservation feature for destination stations (JP6785021). The system first accepts a user’s reservation for a destination, and only when there is an open parking space at the destination, it accepts the user’s e-scooter/e-bike reservation. This prevents users from arriving at their destinations only to find the nearest parking stations full, consequently improving usability.

Although Luup pursues higher density of its stations, there are challenges. In urban areas, the company can only secure limited space to set up its stations, meaning each station needs to come smaller in size. However, smaller stations can get full quickly, and if a user parks an e-scooter or an e-bike at an already full station, that causes trouble for building owners and managers, making it difficult for them to accommodate stations.

Given this situation and the company’s business model focused on short distance and high density, having a feature that allows users to reserve their destination stations is extremely important. By patenting its feature to reserve destinations, Luup has taken the lead in the market. Users cannot reserve destination stations with Docomo Bike Share. One time when I rode their e-bike, I actually ended up in a full station with no place to park.

Conclusion

Even if your product or service is not in sectors like deep tech, there is a big chance you can still create a big economic moat for your company by filing patents one by one for each feature and technology that contributes to achieving PMF.

All in all, when thinking of using patents to create a moat, the important thing is to make the right decision. Does your company have features and positions you want to protect? If yes, what is the scope you are capable of protecting? Is the value you get by protecting what you can worth the resources and cost needed for filing the patents? If the answer is yes and you need patents, you go ahead strategically. If no, don’t file for patents but instead just do your business.

I would like to end this article with the hope that I have given you some hints in making decisions for your businesses.

References

-

How To Choose A Market For Your Startup|Shota Horii (in Japanese only)

-

Zero to One─Peter Thiel

-

Electric Kickboard Operator Luup Raises 4.5 Billion Yen. Short Distance and High Density Business Model Lights the Way to Profit | Business Insider Japan (in Japanese only)

-

Hyper Startup Radio (in Japanese only)

Shohei Hirota

Investment Group

Partner

Patent & Trademark Attorney

Shohei joined GB in 2020. He launched the IP Team and is responsible for IP-related due diligence and support for portfolio startups. Registered as a patent attorney in 2013.